Squats are a favorite lower body exercise for toning and strengthening quadriceps, hamstrings, gluteals, and hip flexors. Because they are so effective, squats are an obvious choice for many workout routines. It’s common knowledge that proper strength training not only builds muscle but reduces the risks of injury and decreases pain in muscles and joints. But what should one do when the exercise intended to strengthen a muscle is difficult and painful to do because of joint pain?

For anyone who sticks to a regular workout routine that includes squats, it will come as no surprise that the most common complaint about this particular exercise is knee pain. Some of you may be experiencing discomfort during or after squats. Feelings of stress around the joint (not necessarily the muscle), feeling as if you aren’t stable during the exercise and generalized joint pain after you’ve completed repetitions are tell-tale signs that something is wrong. This kind of pain can be debilitating for several days, weeks, or even months after you’ve injured the area.

Could you have an injury that causes your joint pain? Undiagnosed, there are many unrelated joint ailments that can be exacerbated by strength training, even if you’ve never experienced pain in your knees before. Arthritis, bursitis, cysts, gout, and untreated ligament injuries can be aggravated during exercises including squats, running, stairs, and lunges. If you think there is a possibility that you have a medical reason for joint pain, it is crucial that you first see a physician about your pain. Because some repetitive movements can significantly worsen these conditions, all physical activity should be approved by your doctor to prevent further injury and unnecessary pain.

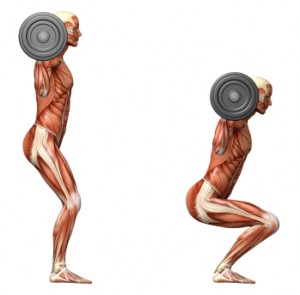

Assuming you have no medically diagnosable reason for knee pain, it is important to recognize that some knee pain associated with squats will be a result of incorrect posture and form during the exercise. Common problems with form and posture include pushing from the toes and not the heels, poor body alignment, and flexion (rounding) of the back. Squats, in particular, can actually strengthen the knees if done properly, so before deciding that they can’t be in your routine, be sure that your form is correct.

The other area of concern with squats is the additional stress placed on the back while doing them. With proper technique, the legs and the hips bear the brunt of the exercise, not the back. Back injuries happen when a squatter rounds their back while squatting instead of maintaining an upright posture during the movement. This is something that can be prevented using good form. It’s also important not to use a weight that’s so heavy it forces you to use your back. Also, make sure not to go past parallel or beyond your body’s range of motion as this will cause your back to round (Flexion) and could aggravate or cause back problems.

Here are some tips for doing squats correctly:

Have you diagnosed any issues with your form? If you don’t have an able individual who can observe and critique your form during the exercise, try to observe your form in a mirror and pay attention to how you feel during a squat. Start with basic squats with no added weight or resistance. Begin with your feet about shoulder width apart and arms extended straight in front of you. Begin the squat as if you’re about to sit in a chair, with your rear protruding behind you and stop when your thighs are parallel to the floor. Observe how you are feeling. In proper form, you should be feeling the tension in your calves, thighs, and glutes. You should not be feeling knee joint pain.

Practice your squatting technique without using weights or barbells until you’ve learned good form. Stand in front of the mirror to be sure you’re doing the movement correctly. Don’t add resistance until you’re completely comfortable with the proper movements – and always warm up before starting to squat.

When performing a squat it is important to know that the further your knee moves forward the greater the stress is on the knee. This is why a powerlifter when squatting tries to keep their knees perfectly still to minimize the stress on the knee and to keep the workload focused on the big muscles of the glutes. The squat technique used by a Power Lifter is slightly different from that of most exercisers and is not the focus of this article. In non-competitive squatting, some forward movement of your knees is fine and desired, but you should never allow your knee to go past your toes and you should try to minimize knee movement as best you can.

To practice not moving your knees too far forward try placing a broomstick horizontally across two chairs (so it looks like a bridge). Then facing the broomstick, position your knees only a couple of inches from the broomstick and practice doing squats without any weight. You can keep your arms out in front of you or even hang on to the chair for balance. Don’t let your knees touch the broomstick during the squat movement and make sure to keep a straight line from your neck through your spine or alternatively focus on one point in front of you. Remember to keep your head still while performing a squat as your body will often follow any movement in your head. If your knees hit the broomstick while practicing your squats try changing your form until your knees no longer hit the broomstick. The best way to do this is to try to keep your weight in your heels. Without a barbell or weights for counterbalance, your feet should try to do a wheelie if you do this correctly.

When you’re ready to try a squat with weights place your feet hip to shoulder width apart with toes turned out slightly with your feet facing out at about a 30-degree angle (this foot position is believed to reduce knee stress). If you’re using a weight, make sure it’s balanced on your traps.

Slowly lower yourself into a squat in a controlled manner to the level where your thighs are parallel with the floor keeping the weight back in your heels during the decent. Instead of thinking of bending your knees, begin the squat as if you’re about to sit in a chair and stop when your thighs are parallel to the floor. Your hips should bend first, not your knees. Keep your back and neck in a straight line during the descent, and don’t let your knees extend beyond your toes. Your back should be at the same angle as your shins at the bottom of the movement. In other words, if you saw yourself from a side view, your back should be parallel to your shins. This will help to keep the barbell centered over your body resulting in less stress on your knees. Make sure your knees don’t buckle in or out during the squat. If your toes are pointed slightly outward then your knees should follow the same alignment path centered over your second big toe.

Once your thighs are parallel to the floor, use your heels to push yourself up to the starting position in a slow and controlled manner. Make sure to inhale on the way down and exhale on the way up and never bounce at the bottom of a squat. Always let your muscles do the lifting, not momentum.

In holding the barbell your grip should be relaxed and you should grip the barbell slightly greater than shoulder width. Your elbows should point downward during the squat as this seems to help to keep the trunk in a straighter upright alignment.

To reduce your risk of injury, never bounce, twist or rock when doing squats, and stop if you experience pain or discomfort during the exercise. Also, don’t do squats when you’re already fatigued.

Are you still feeling pain, even though you’re certain that your form is correct and that you have no other joint ailment? Is it possible that you are over-loading your quads and therefore putting more strain on your joints? If so, consider that an alternative version of the exercise should replace squats in your routine. One of the most common and effective alternatives is a ball wall squat. While still a squat, the major weight of your body can be stabilized with pressure against your back instead of putting the strain on your knees. There are many other alternative joint-friendly exercises that can also be substituted for the squat if you find this exercise causes you joint pain. Many of these exercises will be discussed in more detail in another article as well as be used in my new Low Impact video series.

What are the experts saying about squats and knee pain?

The answer greatly depends on who you ask! While there is no apparent scientific research to attest to it, there are professional trainers and therapists who believe that using parallel squats as the primary exercise for this group of muscles can cause a significant imbalance between the muscles above the knee in the quadriceps. They assert that an imbalance, particularly between the vastus medialis (VM) and vastus lateralis (VL) muscles, can cause stress on the joint and ultimately lead to joint pain. It is further believed that this imbalance can lead to stress in the ligaments and contribute further to the knee pain commonly associated with squats. Contrarily, during an EMG analysis conducted to determine the relative contributions of these two muscles, the National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA) found that there was no significant imbalance in the performance of each of the VM and VL muscles.

Expert studies aside, it’s not a myth that squats are among the most effective, if not the most effective, exercise for glutes, hamstrings, and quads. Without a doubt, squats are one of the best ways to build lower body strength and definition and are known as the king of all exercises. If you are experiencing pain during parallel squats because of a valid medical ailment within your joints, you should always follow your doctor’s advice and avoid activities that may worsen your condition. If, however, there is no medical reason for your pain, it’s worth the extra analysis to discover the exact cause of the pain in your knees. It may be that the only obstacle between you and strong, toned muscles is your form, weight load, and stance! The good news? Most people without orthopedic problems can do squats safely if they use proper form and for most others, there are alternative exercises that can be substituted.

References:

Deep Squats. Jason Shea PICP III, MS, C.S.C.S.

Fitness Prescription for Women. December 2010. Page 20.

Strength and Conditioning Journal. April 2011

Related Articles By Cathe:

Squat Tips: How to Get the Most Out of Squats and Avoid Injury

5 Common Squat Mistakes You Could Be Making

The Surprising Fitness Benefits of Half Squats

Squat Depth: How Low Should You Go?

Front Squats vs. Back Squats: Does One Have an Advantage Over the Other?